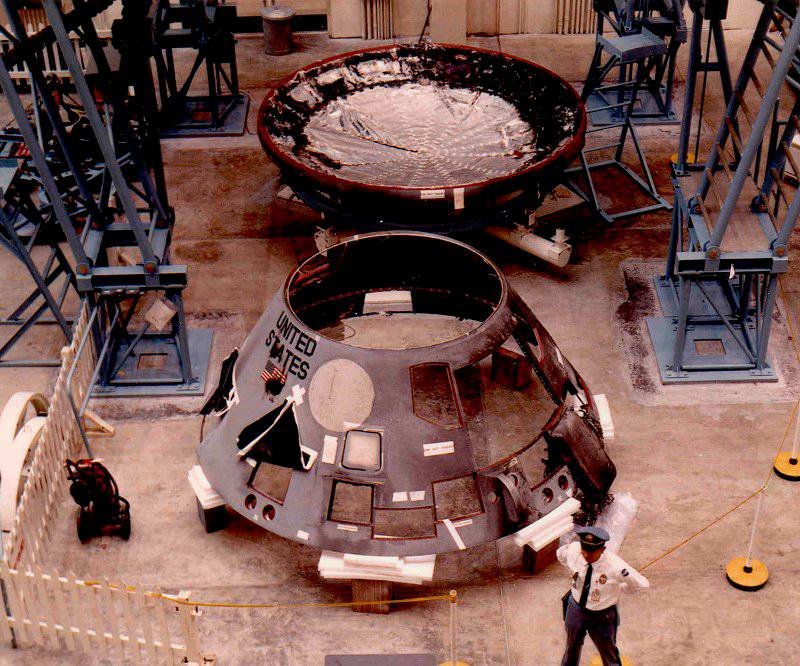

In 1967, three astronauts were burned alive during a test of the Apollo 1 spacecraft. It was a defining moment for NASA, the agency charged with carrying out President Kennedy’s vision of landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade. The language that emerged in the wake of the disaster is telltale. In the investigative report that followed there was no mention of culture. There were no conversations about human failure or culpability. Instead, they seemed to regard it as a problem with the inanimate inner workings of industry and science.

Here’s an excerpt:

“The Board’s investigation revealed many deficiencies in design and engineering, manufacture and quality control. When these deficiencies are corrected the overall reliability of the Apollo Program will be increased greatly.”

In other words, the machinery was wrong. Human error didn’t become the focus of causality because human error was to be expected. Human error wasn’t something you resolved through any business disciplines that existed at the time. The answer to the organization’s problems, they reasoned, would be found in the machinery at the center of the organization, not among the people who run it. The machinery was the centerpiece. The employees were just the outer layer.

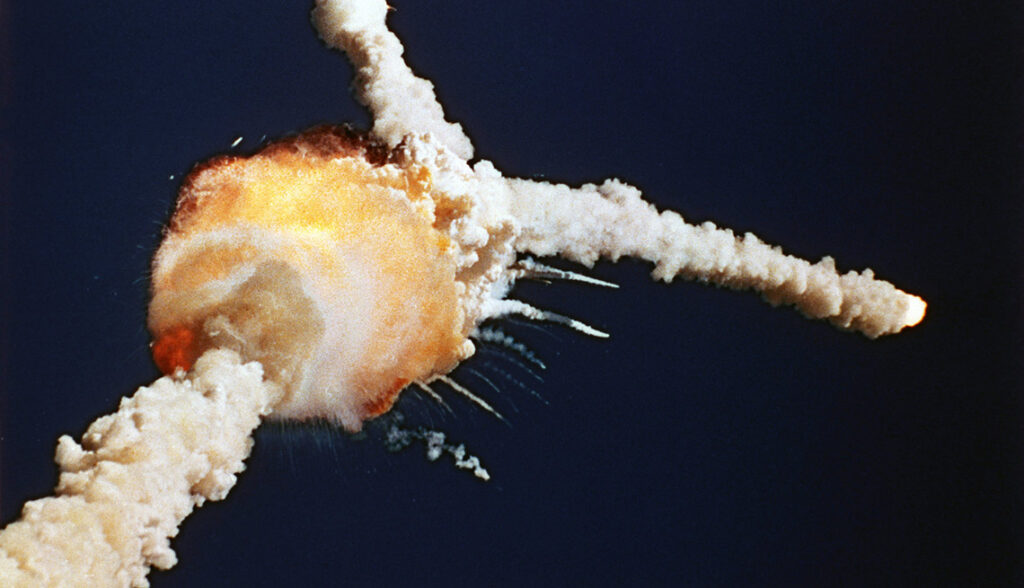

NASA continued to send people into space throughout the decades that followed, but it wasn’t without additional casualties.

Once again, a review board was assembled to investigate. But this time the language used to explain the cause was notably different. While the report detailed the engineering-related failures, the board added a whole section about the culture of NASA as a contributing factor. Compare this to the language used just three decades earlier:

“The organizational causes of this accident are rooted in the space shuttle program’s history and culture, including the original compromises that were required to gain approval for the shuttle, subsequent years of resource constraints, fluctuating priorities, schedule pressures, mischaracterization of the shuttle as operational rather than developmental, and lack of an agreed national vision for human space flight. Cultural traits and organizational practices detrimental to safety were allowed to develop….”

In all, the Columbia report contained 137 uses of the word “culture,” whereas the Challenger report contained none. Zero. This attention to culture highlights a monumental shift in thinking, not just at NASA, but across the global work force. The machinery was no longer the hero it once was. Instead, the machinery was taking its place within a larger construct, one that better explains what an organization is and how it functions. I’d like to suggest that culture is the concept that best defines how the various components in an organization come together and relate to each other. It’s not just a reference to people, but it’s also everything those people produce as organizational artifacts. And it includes the machinery itself which, after all, was also created by people. The term culture is the holistic encapsulation of the organizational entity. It’s the summation of all its characteristics.

Culture means everything!